Nothing is Infinitely Faster than Something

What NPM taught the Javascript community

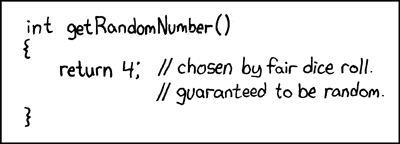

Any time you can compress a calculation into a constant is a run-time and test-time gain.

Assuming, of course, that you still meet the requirements of that calculation.

The apocryphal example of turning a massive calculation into a very small one with a few constants and a fixed number of calculations is the tale of Gauss and his elementary school mates being told to add the numbers 1 to 100 as busywork, essentially:

var n = 100;

var sum = 0;

for(var i = 1; i <= n; i++) {

sum += i;

}

Gauss recognizes the pattern in the input series and simplifies it down to just:

var n = 100;

var sum = (n*(n+1))/2;

Most of the time, we don’t need to be as clever as Gauss, because a for loop of a hundred or a thousand calculations will complete faster than we can type it, and far faster than we can think of the better solution.

This is the “run-time / programmer-time” trade-off that has increasingly skewed towards programmer-time as computing power has increased over the years, and is the foundation of the entire jQuery project, for instance, where the sometimes significant performance penalties matter less than the extra developer effort to deal with the variations in the DOM API implementations across browsers (and eventually, the effort to know the DOM API over the jQuery API).

But if all I’m interested in is one small piece of what jQuery can do, why should I have to pull in all of the rest of it, and why should I have to pay the performance penalty of the jQuery $ function that checks if its getting an element, a string, an array of elements, an array of strings, etc before it can operate on my values that I’m now setting with a method call and a throw-away object construction, why should I pay such a high price?

The developers at imgur only wanted DOM construction from jQuery, not the “query” part of it at all, and wrote a library, ThinDOM, to get roughly 10 times the performance of jQuery.

This is an example of a trend in the Javascript community that was kicked-off by NPM and the Node.js community: many micro libraries that do one thing very well and used together. Learning lessons from the Python and Ruby communities, NPM is a bundler-style package manager, which means basically two things:

- Each library/module that you include in your project has all of its dependencies private for itself (unless NPM sees duplicates, then it shares them).

- You control the namespacing of the modules you use, so namespace collisions are impossible (except for publishing packages, but there are many module users to authors).

This means that you don’t have to worry about upgrading any module affecting any other module just because they have common dependencies – if Module A and Module B use common Module C, and the upgraded Module A uses Module C v2.0 and Module B is still on v1.0, they’ll just have their own copies of Module C at the specified version and you’re golden.

This relieves both the developer and user of the module from worrying about dependencies they’re using, so people are more likely to reuse more code. Further, the code that is being reused is more likely to be smaller in scope, as an increasing number of modules means to grok them all the comprehension complexity of any one of them needs to be minimal, and similarly the code complexity should be small-ish if there’s worry of many duplicates of the code at various revisions in the dependency graph. This makes justifying a large-ish monolithic library like jQuery more and more difficult.

These smallish modules are therefore easier to optimize for performance if they see a lot of usage or are used in a tight loop; even if the module needs to be essentially rewritten to meet the performance requirements, the reduced scope and total code size makes that tolerable.

At my job we get to do that fairly often, and usually we’re allowed to open source these efforts, too.

For instance, there is a pretty efficient Point-in-Polygon implementation in Node.js called point-in-polygon that we use, but our polygons don’t change frequently, and we have been querying this more and more, so a colleague of mine wrote a library called in-n-out that grids the cartesian rectangle surrounding the polygon and precalculates whether a particular rectangle is entirely within the polygon, entirely outside, or intersecting the polygon and falls back to run-time calculation, trading memory for a roughly 20x perf improvement.

Similarly, I wrote a value-to-gradient linear interpolator to replace usage of tween.js’s linear interpolator named rainbow-dash, which assumes the gradient to be interpolated over will be queried many times and caches the interpolation constants on construction (it also allows arbitrary distance between color stops just like CSS’s linear-gradient, too), producing a 30x perf improvement and 4x over the best <canvas> can muster.

You probably don’t personally care about point checks on arbitrary polygons or really-fast color selection, but I’m sure there are bits of your stack that you wish were faster, and a stack built out of many small libraries is much easier to tune than a single monolithic library. Never needing to load code you’re not going to use, replacing chunks of code you need to be fast with an optimized version, all while still being able to just require almost everything you do need – that’s a wonderful place to be.

Don’t let the number of requires bother you; instead, think of the “negative space” of lines of code and architectural constructs those single-purpose libraries give you versus some framework that magically does it all (and so much more than what you need). All of that “nothing” is infinitely faster than “something” in its place, both run-time and developer-time.